On the morning after I was born, on March 20, 1921, in the tiny western Oklahoma town of Oakwood, my dad wrote a letter to my mother’s two sisters in Oklahoma City, saying, “We will not be naming our latest offspring after his Aunt Elizabeth or his Aunt Mary, as we do not think those names, grand as they may be, are fitting and proper:

“IT’S A BOY!”

Years later, I reread the letter and decided that whatever talent I might have as a newspaper reporter must have been inherited from him. After all, he had a big story there, and he had a pretty good lead, he got the facts straight and he spelled the names correctly. And who knows? He may have coined the phrase that lives forever on greeting cards and cigar bands.

I was born on the kitchen table of the town’s only doctor, Edwin Sharpe, and I started life peacefully enough. I barely remember the booster trains that would come from big towns like Watonga and Custer City and throw candy to the crowd while inviting everyone to visit them and shop.

I also have vague memories of playing cowboys with my two brothers and Rollin Shaw, who lived next door. Usually, I was a bad guy and they would tie me to the windmill.

I have a stronger recall of the night the Klu Klux Klan burned a cross in our front yard. It was, and still is, the worst thing that ever happened to our family, and it was all because we were Catholics – the only Catholic family in town. I was too young to remember it all, but my two older brothers told me about it many times.

As the cross burned, my mother, crying, pleaded with my Dad not to go outside, but he went out on the porch and confronted the Klansmen. He told them they might as well take off their white sheets and hoods, because he knew who they were. He also offered to take any of them on

The Klan spokesman responded by warning my Dad he had better pack up his family and get out of town. He added that starting the next day, my Dad’s drug store, the only one in town, was boycotted.

In the days that followed, while my Dad and Mom were facing up to the fact we had to move, some of the town leaders came to my Dad and told him, almost tearfully, they were sorry they participated in the cross burning, or that they did nothing to try to stop it.

We were singled out because we were an undesirable minority, and over the years, in my newspaper career, I’ve had to laugh when editors have lectured me on the fine points of discrimination.

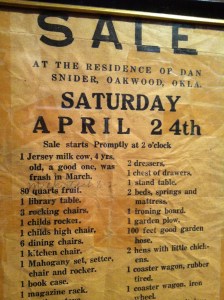

We had no choice. We had to get out of town, and to do that we had to sell almost everything we owned, including a Jersey milk cow, chickens with baby chicks, furniture and my mom’s few household treasures. We were sent on our own Trail of Tears – uprooted and told to get to our new home the best way we could.

We did it in a Model T Ford touring sedan, meaning it had a cloth top and button-down windows. It was crammed with what we could get in it, and I’ve heard many times all the stories about the nightmare of our slow and miserable trip from Oakwood to Wyoming, and a tiny speck of a town called Veteran, where my mother had relatives and a general store needed a proprietor.

The ironic thing is that my dad, Daniel William Snider, converted to Catholicism so he could marry my mom, Leona Frances Shively. I don’t think that he was ever sorry he did it, and they both had come a long way to the point where they met and were married in western Oklahoma, in a church that now is a farm storage building, in Anton, a town that no longer exists.

Our forced departure was the second upsetting event our family went through in a short span. A year earlier, my mother discovered a lump in her breast, and eventually had to go to Oklahoma City for the operation. Her entire breast was removed, even though the growth was benign. This was in 1925, when I was four.

My dad and mom met in Custer City, about 25 miles south of Oakwood. His family had moved to the area from Indiana, by way of Miltonvale, Kan., where he was born. Her family also came from Indiana, by way of Howe, Neb., where she was born. They both are buried in Oklahoma City.

We were on the road several days, including interruptions for flat tires and rain that made the “highways” impassable, covering the roughly 700 miles to Veteran. Fewer than 100 miles of that was paved. The rest was “improved” roads, meaning gravel; “graded” roads, meaning some of the ruts smoothed out; and the last dreaded category, “dirt or poor” roads, and they weren’t kidding.

It was a little before dark when we arrived and we spent the night sleeping on grain sacks in the store my dad was taking over. Next day we saw Veteran in all its splendor, dominated by the Great Western Sugar Beet Co. mill, sitting high on the prairie. The rest of the town included a few stores, a garage that sold gasoline, a lumber yard and a creamery run by a man named Izzy.

Standing alone on one end of the town was the building where my dad would be postmaster, and also sell feed, seed, coal, clothing, groceries, hardware and so on.

At the other end there was a large irrigation ditch, feeding smaller ditches that led to the land where sugar beets were grown. Some grew as big as footballs, and at harvest time Mexican “beet-toppers” would show up. They’d pull the beets, cut off both ends and throw them into wagons that would haul them to the Great western. What happened there I don’t know, but the Union Pacific tracks ran alongside the mill, and trains would stop and carry off whatever it was.

Grim reality quickly set in for the Sniders, and I still wonder how we survived. Our first home there was a one-room shack a mile from town. It had a stove, a table and some chairs, and a bed. Under the bed were springs and a mattress which were pulled out each night, and that’s where my two brothers and I slept each night.

My dad rode a horse to work, and my two brothers rode a wagon or sled to school. The sled used in the winter was pulled by two horses and was pretty neat, but the blizzards that made it necessary weren’t. Our shack was so small that one storm left it completely covered with snow. My dad had to claw his way out a window to get help. Neighbors fought their way through drifts to dig us out, and the path they dug to our front door was described by one of them as “deep enough to hide a horse.”

The winters were one thing, but the summers had their moments too, like when we’d find a rattlesnake and my mom would come and kill it. That’s why we considered it a gift from heaven when my dad found us a house in town, and we moved there before the second winter arrived.

* * *

Living in town, even in Veteran, was a whole new life. By the time the second summer came, my brothers and I had a horse. She was an old workhorse, but perfect for us. She’s stand in the center of the big irrigation ditch, her head and rump out of the water, and let us dive off of her, and then pull ourselves back on by using her mane or tail.

When I was alone with her I’d lead her to a fence where I could climb up and then slide on her back. Then, we’d plod all over town, and give neighbor kids a free ride. She got out of low gear only once. Something spooked her, and she bolted with a burst of speed I never realized she had. I went flying off, and when I got up out of the dirt I wasn’t sure I ever wanted to ride her again. But I did.

The horse was kept in a corral and barn behind my dad’s store, and one morning she had a swelling just above the hoof on the front leg, which dad said had to be a rattlesnake bite. He put some red crystals in a tub of water, put the horse’s leg in it, and it seems now that old mare stood there for hours each day until the swelling was gone

She was something. I wish I could remember her name.

* * *

Veteran apparently didn’t have a Ku Klux Klan, and maybe it was because it had a very active American Legion. While we were there the Legion built a large new building, big enough for any kind of social event the town could dream up. The Legion Hall became the center for a variety of activities.

It was a building that was half underground, so construction started with digging a huge rectangular hole about 10 feet deep. I spent a lot of time watching men handling metal scoops, pulled by two horses, taking dirt out of the hole. And, as the hole got deeper, there were more warning signs, and makeshift fences, to stop people from falling in.

The fences didn’t work for dogs. We had acquired a couple of great dogs after moving to town, and they spent most of their time roaming the town and the prairie around it, and, in summer, playing in the irrigation ditch. One night my mom called them to eat, and they were on the far side of the Legion hole. In the dark, they came streaking for home.

I was told they were both found next morning on the bottom, dead. I still don’t see how that could have happened to both of them, so maybe they were hurt so badly they had to be put away. Whatever happened, they deserved better.

* * *

My mother’s relatives in Veteran included her Aunt Maude Courtney, and Cousins Forrest and Joe Courtney. We never saw much of them, except for the holidays, when we would be invited to Aunt Maude’s house to eat. One of these occasions was a Christmas when the few Catholics in town, Aunt Maud among them, arranged for a priest to come from another town and say Mass – probably at the Legion Hall. Aunt Maude didn’t go, saying she was too busy cooking. My mother couldn’t believe it, and prayed a lot for Aunt Maude after that.

Forrest Courtney was a successful beet farmer, and got into politics. After we were gone from Veteran he was elected several times, but I don’t know to what office, or from which party. Joe owned a grocery store, and when I’d go there to get something for my mom, he was nice to me. He had a distinctive laugh; he’d laugh for a while, then suck in his breath and start over.

One memorable day, the two of them drove their old cars to Cheyenne, and came home in two new Overland sedans. It was most awesome display of wealth I’d ever seen, and I remember wondering if my brothers and I would ever have new cars.

* * *

The Sniders seemed to have settled into life in Veteran, and in later years often speculated on what would have happened to all of us if we’d never left. There wasn’t much promise in any of the guesses. My mother was happiest over our escape, because I was ready to start school and she desperately wanted her sons to attend Catholic schools.

My older brother, Dan, already was in Oklahoma City, living with our Uncle Bill and Aunt Mary Garthoffner, and going to school at St. Joseph’s.

Uncle Bill and Aunt Mary, along with my mom’s other sister, the one everybody called Buel, who also lived in Oklahoma City, began putting the pressure on mom and dad to move back there and start over. They finally agreed to do it, and that’s how it happened that I started kindergarten at St. Joseph’s.

We made the trip from Wyoming on the train, which was pretty exciting. We changed trains inDenver, which meant that in a few hours after we left Veteran, I had seen more people and more cars than I had seen in all my life before that.

And, I have been told many times, that soon after Uncle Bill picked us up in Oklahoma City I shouted, “Hot tamales, I see a streetcar!” Another country boy was becoming a city boy.

My dad got a job selling candy, and while making his rounds, discovered a drug store for sale in Britton, a town of about 1,000 that at the time was about five miles north of Oklahoma City. He took it over, and we bought the house where my brothers and I grew up. Britton had one other Catholic family, and no Klan.

The house had what was for us an incredible feature. It was the first place we had ever lived, other than the apartment, that had indoor plumbing. It actually had a bathroom with a stool, which meant no more trips to the outhouse in the dark or in the snow. The first time my brothers and I saw the bathroom, we were so elated we all used it at the same time, and I remember my brother Dan saying, “I’ve got dibs on flushing it.”

I really believe our lives as individuals began right there. We had stability and caring parents, and we could go in about any direction we chose. We chose a lot of them.

Dan became an executive in motion picture distribution, first with RKO and then Universal.

Al was a Navy pilot in World War II and, when the war ended, he flew for United Airlines and later with Pan American before returning to the Navy, staying until he retired. He also is retired from Texas Instruments.

It seems I never could find a steady job. I worked for seven newspapers, the FBI, NCAA Films and the CFA (College Football Association). I have been with two oil companies doing advertising, PR work and lobbying. And I put in seven years with the Lord and Legend of Oklahoma football, Bud Wilkinson, first as Bud’s administrator on President Kennedy’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports, next in his campaign for the U.S. Senate and then in a venture we called the Lifetime Sports Foundation.

Britton changed almost everything in our lives, but we never forgot what we left behind in Oakwood and Veteran. My last visit to Veteran was in 1985, and the town had all but disappeared. The one store that remained was the one my dad ran, and it looked about the same as it did when we left some 60 years before. The man running it had been there a long time, and he said he remembered hearing of the Snider who once was in charge.

The sugar beet mill was still there, and he said it was still operating, but all that remained of the Legion Hall was the foundation. The rest of what I remembered about the town was just gone, and I wondered again where the Sniders would be if we hadn’t left when we did.

My middle brother Al, three years older than I am, and I visited Oakwood in 2000. It is still alive, but just barely. It has no stores, no schools, no bank and no church, and maybe 100 residents. About a quarter-mile up a dirt road from the town there’s a highway, and a Phillips 66 station with a restaurant.

I had called ahead to Rollin Shaw, the kid who lived next door to us, and he met us there. He was in his 80s, and he took us on a tour, telling us what us what had happened in the years since we left. We sat in his car for a long time, staring at the foundation of our old house, and the tiny front yard where the Klan burned the cross.

There was no healing, or so-called closure for me. It just made me think again that no family – white, black, brown, yellow or what have you – should ever be treated that way by anyone, and particularly not by a bunch of ignorant jerks.

Rollin never talked about the cross, and we didn’t ask him. What good would that do? He died a few months after our visit.

* * *

Britton was a typical small Oklahoma town, featuring a Main Street and a lot of churches, one of which stands out in my memory.

The Hadleys lived on a small farm north of town, and in the summer, Mrs. Hadley would come to our neighborhood often, selling eggs, fresh fruit and vegetables from a wagon she pulled. My mother became a friend and regular customer and the two of them always had a good visit.

One day Mrs. Hadley told my mother her daughter had a new baby girl named Halad, which she pronounced like salad. My mother said that was a pretty name and Mrs. Hadley nodded, saying it was from the Lord’s Prayer. “You know,” she said, “Our Father which art in heaven, Halad be they name. . . “

In return, undoubtedly, God soon caused oil to be discovered on the farm and the Hadleys, now wealthy, thanked Him by building a new church just offMain Street, and they bought a fleet of new Ford sedans to haul worshipers from near and far for services.

* * *

For religion, the Sniders had the best of both worlds. There was a Catholic church and school close by inOklahoma Cityand our house in Britton was across the street from the Nazarene Church. We could hear them chasing the Devil out of their lives in Sunday morning and evening services and at Wednesday night “prayer meeting.”

Every summer they would erect a large tent on a vacant lot that also was across the street from us and hold a two-week “revival meeting.” They packed ’em in.

* * *

My dad’s drug store was on Main Street between Harry Wilson’s barber shop and Art Hobbs’ grocery store. Unfortunately, it also was beneath the town’s meeting hall, where all the civic and social groups held their meetings. Some of them sang, but the worst activity, from our standpoint, came from the ladies of the Eastern Star, who marched a lot and caused dust to be jarred loose from the ceiling and descend in clouds to the merchandise below.

My dad could fight back. He had a big Philco radio near the front of the store, hooked to two outside speakers. However, the only time he’d turn it on was for a sporting event or a political happening, but after a time, the Eastern Star learned not to schedule a meeting on the same night as, for example, a Louis-Schmeling fight.

It wasn’t necessarily good for business, because real customers had a tough time getting through the crowd that gathered just to listen.

* * *

My dad liked sports and the people who played. Any time a Britton High team won a game, he gave all the players a double-dip ice cream cone. He was a soft touch, and often treated “players” who never played or who weren’t even at the game. He cracked down one night, asking, “How could there be 18 players on a basketball team?”

It was through these treats that I met all my Britton High idols, guys I still remember, like Royce Jones, who played without a helmet; the McGrew brothers, Pat and Mike, who were giants; the Checotah brothers, Ben and George, Indians from the Baptist Orphanage north of town; Leo Cain and many more.

The other Catholic family in Britton included Charlie Davis, who was a top athlete at Britton High before transferring to the Catholic school my brothers and I attended in Oklahoma City in eleventh grade, starring in both football and basketball.

Charlie and my older brother, Dan, who was five years ahead of me in school, were teammates. Some Britton boys and their parents thought the two of them felt they were too good for Britton High.

In Dan’s senior year, I was their biggest fan and was fully aware of the resentment and hostility some Brittonites held for them. So, imagine my reaction when Dan, out of the blue, said our Oklahoma City school and Britton High had scheduled a basketball game, to be played the following week, in Britton.

First, I was stunned. Then, when it had sunk in, I was afraid the local boys would embarrass the snobs who were too good for the town school. It got worse when the Oklahoma City paper played up the game, and even ran pictures of Dan and Charlie. I thought about not going, of hiding until it was all over.

But I went, and prayed: Lord, please don’t let them get routed. They didn’t; they won. They beat the locals, and since there wasn’t anyone there to root for them, I enjoyed it in silence, in the middle of the local fans, and didn’t let out a peep.

No kid could have been more proud of his big brother and Charlie, than I was. I felt they had gone boldly into the camp of the enemy, risking ridicule and humiliation, but had instead gained stature and respect.

As far as I know, it was the only time the two schools ever played.

* * *

This is what I call a Brittonism: Charlie Davis was prematurely bald and it started in high school. One day in the drug store, I heard some men talking about him, and one said it was a shame that Charlie was losing his hair. Another agreed and wondered why it was happening.

A third man offered an explanation. He pointed out that Charlie participated in sports year round and probably took a shower every day, or close to it. “That water,” he said, “pounding down on his hair that often is causing it to fall out. I’ve heard of it happening to other men who took too many showers.”

For years after that I never let water from the shower hit me directly on top of my head. I protected my hair with my hands while shampooing, and I may still do it, without knowing it. Don’t laugh. I’ve still got a lot of hair.

Here’s another Brittonism: Britton didn’t have a public restroom, and for some reason – maybe because he was the friendliest merchant on Main Street– most of the men needing to answer the call of nature would come in the drug store and ask to use the facilities. My dad would frown and shake his head, but would tell them to go ahead to the back end of the store.

It always upset him, and one day he decided he’d had enough. He called Britton’s top handyman and the next day, construction started on a public outhouse on the vacant lot between Art Hobbs’ grocery store, which was one door west of the drug store, and Britton’s only movie house.

They dug the pit, built the structure over it, anchored it so it wouldn’t blow away and put on door latches, inside and out. It was a one-holer, all that was needed. It didn’t have a sign on it, but everyone knew what it was.

A couple of days later, a woman said to my dad, “Dan Snider, you’re a saint! You’re always doing something for this town.”

He smiled modestly, and didn’t tell her he did it to keep the town out of the back end of his store.

* * *

Our wide, four-laneMain Streetwas the domain of City Marshal Leland Corbett and what upset him most were drivers making U-turns. He was a John Wayne type of man, and he’d whistle down the violator, approach the car and open the conversation by yelling, “What the hell do you think this is – a cow pasture?”

If the violator was an out-of-towner, whoever happened to be onMain Streetwould gather. Some merchants would forget customers long enough to go out on the curb to watch. Very rarely did Marshal Corbett have to arrest and cuff anyone, but if it happened you’d want to see it, and later tell those who didn’t, “’Ol Leland got another one. Had him out of the car and the cuffs on him before he knew what was happening.”

When my dad closed the store at night, he’d put the cash in a cigar box and walk home, which was about six blocks. In bad weather, the Marshal would often give him a ride. I never heard of a holdup, or a serious crime of any kind happening in Britton.

When I became old enough to drive, and was working late in the store, my dad and I would cruise out to the two-mile-corner east of town. He’s smoke a cigar and drink a beer, and we’d talk. Those were great nights. My dad, incidentally, didn’t know how to drive a stick shift and didn’t learn until he was about 60 years old.

* * *

I started working at the drug store as soon as I was old enough to hop cars and carry ice cream cones and fountain drinks out to our curb. I learned a lot about life, seeing and listening to the people in those cars as I served them; in fact, if my mother knew what I was exposed to nightly, my car-hopping days would have ended.

It was particularly educational when a carload of Britton teenagers would drive up and order cones or cokes or whatever. I was a perceptive lad, and I figured what those Britton girls and boys were doing was necking (a word I’d picked up on the school playground). Looking back on it, I deeply regret that I moved away before I was old enough to take a Britton girl for a ride in a car.

My pay was 10 cents an hour, but over the years, I advanced in the organization to the point I worked for nothing. This was after my brothers left home, and I would hold down the fort alone while my dad took times off to go to church or maybe to the barber.

Some customers were nervous when they saw I was there alone. I remember the first time I sold condoms. The man asked for a package of Peacocks, which was a brand name, and when I told him I didn’t know where they were, he said he’d show me and tell me the price. He pulled them out of a drawer in the back room and gave me the money, but he never told me what they were for. I learned most of that kind of stuff at school, on the playground.

* * *

I also learned a lot delivering the daily Oklahoma City Oklahoman and Times to one-third of Britton. For one thing, I learned the world has plenty of liars and phonies. The price for delivery of the morning paper and the Sunday paper or the afternoon and Sunday paper, to the door was 18 cents per week. The morning-afternoon-Sunday combination was 25 cents. I made six cents on the 18-cent deal and seven cents on the two bits. I had to collect it personally every week, and I’d always have a dozen or so lying deadbeats tell me I’d have to come back later to get the money, for one fake reason or another.

After a year of this, I adopted a “no money-no paper” policy, and when the circulation manager said I couldn’t cut off customers so abruptly, I quit. I missed it, because when you walk the neighborhoods at four in the morning and in the late afternoon, you make a lot of friends – all kinds of friends.

* * *

I made friends with most of the boys my age in Britton. Across the street from our house was a vacant lot where we played football and baseball (or softball), and there was a backboard and hoop attached to the top of our garage for basketball. Almost every day, weather permitting, there was a game going on.

We also took hikes in the country, where we’d smoke “Wings” or “Twenty Grand” cigarettes that were 10 cents a package, or three packages for a quarter. The Twenty Grands had a picture of the famous racehorse on the package, and we used to say it was a picture of the factory where the cigarettes came from.

One of my friends was Ben Hawk, whose family was very active in the Baptist Church. Ben wanted me to come to a meeting of the BYPU, which was the Baptist Young People’s Union, except that the cool cats among us said the letters stood for “Button Your Pants Up.” Still I asked my mother if I could go, and I thought she was going to faint. In the end, though, she let me go, and all that happened was that they sang a special welcome song to me, and served me punch and cake.

Another good friend was Alva Rollins. We wound up going to school and playing basketball together atOklahoma CityUniversity. Other names I remember include Ora Hickman, Jenks Presley and Delphin Motter. How could I forget them?

* * *

One of the nicest men in Britton was Captain Melvin Sellmeyer of Braniff Airways. The deal was that Braniff had its maintenance facility at Wiley Post airport, two miles from Britton, and some Braniff pilots lived there because they often would pick up their plane at the Wiley Post and fly it down to Oklahoma City Municipal to board their passengers.

Sellmeyer is one of my all-time favorite heroes. He lived on my paper route and was a regular customer at the drug store. He always smiled and spoke to me as I started with awe at his Braniff uniform, and his image of courage and daring.

Then it happened. One day he took off fromDallas, bound forOklahoma City, and a wheel from the fixed landing gear of the single-engine Vega airliner fell off. It meant he’d have to land on one wheel, and with a crowd gathered to watch, he did it perfectly. He touched down on one wheel and didn’t let the other side hit until the last minute. Nobody was hurt, and the plane wasn’t severely damaged.

Next morning, his feat was all over the front page of the paper, and at school, I talked about it all day, always adding, “I know him. He’s a friend of mine.” I was about 10 years old.

* * *

Another of my heroes I got to know in Britton was my Uncle Bill Garthoeffner. He was a traveling salesman, peddling Hickock “Belts, Braces (suspenders) and Garters.” The brand was the Cadillac of the industry, and they later added men’s jewelry and leather coats. Uncle Bill made so much money that during the Great Depression, he and Aunt Mary built a three-bedroom, two-bath (unheard of) brick home inOklahoma Cityfor $5,000 cash (unheard of).

Before that, Uncle Bill and Aunt Mary, and Cousin Bill Jr. lived in Britton, just two doors from us. Uncle Bill liked to visit Wiley Post airport and frequently took “the kid” with him. One day, I couldn’t believe it when he walked out of the hangar office in a flying suit, with helmet, goggles and a parachute, and climbed into a biplane with an instructor pilot and took his first lesson.

He hadn’t told anyone – not even Aunt Mary – but he went on to become known as the county’s first flying traveling salesman, and owned, one at a time, nine airplanes with “Hickock” painted on the fuselage.

Uncle Bill was handy with engines and always took care of his planes and autos. He also was especially good with woodworking tools, and I remember one of the best days of my life, when we first arrived inOklahomafromWyomingand lived for a short time in the Garthoeffner apartment inOklahoma City.

He asked me to help him build a couple of bookcases, and I happily agreed. We did it on the fire escape of the apartment house, and I helped by holding something, handing him something, or fetching something he needed. It took all day, but when it was over, he had two great-looking bookcases, about four feet high and 18 inches wide.

He stained them a dark color, and I’d never seen anything prettier. Maybe I’m exaggerating, but today, we have one in our living room and our daughter Amy has the other in her home inTexas. When “we” built them, I was getting ready to enter first grade.

Uncle Bill’s territory for Hickock was Oklahoma and parts of Texas, Arkansas, Missouri and Kansas. In the summertime, after I got older, he took me on a few of his selling trips. I’d help with his sample cases and try not to listen when the buyers told him dirty jokes. On the highway, he’d tell stories, often about being in World War I and, believe it or not, we’d sing duets. We weren’t bad.

* * *

Uncle Bill was generous. When the Hickock line would change, he would give his outdated sample belts to me and my brothers, and as a result, the Snider boys had the fanciest belts in town, or in school. It was too bad we didn’t have the trousers to go with them. My wardrobe always was about 90 percent hand-me-downs.

As I neared high school, I dreamed of having my own car, and Uncle Bill made the dream come true. What happened was that there were several farm yards around the airport, and one day as he was making a landing, he spotted an old Model-T Ford parked in one of them.

He landed, drove to the farm, bought what was left of the car for $10 and had it hauled to the Britton Salvage Yard. It so happened that the owner of the Yard owed my dad’s drug store a considerable amount of money, so we made a deal that he could work off the debt by working on the car in his spare time.

A few weeks later, I had a Model T with Chevrolet disc wheels; a self-starter, very rare in old cars; four seats; a cargo box in back and – no roof. It was topless.

I was the proudest kid inOklahoma, and the envy of all who saw the vehicle. Girls couldn’t wait to take a ride in it, and I had it made as long as it didn’t rain or get too cold.

In the summer of 1936, before starting the 10th grade, Joe Trosper, Leonard Link and I took a trip in it toDallas andFort Worth for the Texas Centennial Fairs, and to Arkansas and Eastern Oklahoma for camping and swimming at state parks. We had a little money, but we overspent on the girlie shows at the Fairs. We were saved by the large assortment of canned food in the cargo box we had taken from home. We were long on peaches and tomatoes.

Link would become the center on our championship basketball team at St. Gregory’s, which you’ll hear about later. He also was the first of our group to die in World War II, when his destroyer was hit by Japanese shells from a Pacific island.

* * *

The years in Britton were mostly pleasant, but unfortunately, they ended on a sour note. From the beginning, the post office had been in my dad’s drug store, in the back end, and there was no home delivery. It meant that most Brittonites would make at least one trip through the store per day to look for mail. Good for business.

Then, in the late 1930s, Democrat Josh Lee was elected to the U.S. Senate, and his promise in Britton if he won was that he’d move the post office out of its Republican roost and into the drug store of our competitor, Democrat Dave McLemore.

He kept his promise, and business at Snider’s started to slip. On top of that, our store always was famous for low prices, ice cream cones so big that we lost money on every one of them and for easy credit. My dad would let you charge a candy bar, a package of cigarettes or a magazine as fast as we would an expensive prescription. We had a lot of money on the books and those kinds of people aren’t known as fast pay or any kind of pay unless it was forced.

Dad stubbornly refused to turn the delinquents over to a bill collector and finally it caught up with him. He had no money to pay the wholesale houses, so they shut and locked our door. We were out.

I was sad, for a while. My dad swallowed his pride and went to work for McLemore, and that had to have been tough. I was proud of him, and made it a point to go into McLemore’s store every chance I had, and say howdy to him. His old store never reopened, and McLemore had a monopoly, even after Britton got a free-standing post office. Fortunately, dad’s suffering didn’t last too long.

Dr. Grady Matthews, State Health Commissioner, lived in Britton and was a friend of my dad. In short order, he added him to the field staff and he and my mom moved to Durant, in southeasternOklahoma. My mom liked it immediately, because she would walk to mass every morning. The only hitch was, dad had to learn how to drive.

* * *

It turned out that Aunt Mary, who was Uncle Bill’s wife and my mother’s sister, and who lived just two doors from us in Britton, was the unanimous choice to teach my dad to drive. They weren’t perfectly paired for this assignment, because Aunt Mary thought dad was a bad influence on Uncle Bill when it came to hitting the one brew. It was plentiful, because dad usually had a batch bottled and ready and another batch working. And, they both liked it. With a name like Garthoeffner, how could you not like beer?

So, Aunt Mary and dad took our family stick-shift Chevy out on some country road and started the lessons. After the first one, they returned and it looked like they weren’t speaking. When asked how it went, he just grumbled. It was obvious he wasn’t comfortable with the arrangement.

But, mom convinced him that the quicker he learned, the sooner it would be over, so he stuck with it. He learned to drive, in the country and in town, even inOklahoma City, which was big-time driving.

I eventually rode with him, and noticed he developed one habit. When a car would pass him, or slow down in front of him, or a driver would signal a turn, dad would mutter, “now, I wonder what this damn fool is gonna do?”

He always drove slowly, and I don’t know that he ever had a mishap of any kind. It was good that he didn’t. I was visiting mom and dad one time, long after he started driving, and mentioned insurance. They looked at each other, and I knew they didn’t have any. Thirty minutes later, they did.

* * *

One other note about my dad. Although he spent much of his life in the drug store business, he never had a pharmacist’s license. He learned to fill prescriptions in stores owned by his brothers in westernOklahoma, and the store he bought in Britton was owned by an elderly man named Robinson.

He was an interesting package. In addition to owning the drug store, he was a physician, a pharmacist and the postmaster. In the sale, which, incidentally, took place when he was 84, the deal was that he would remain the store’s pharmacist – if someone asked. If someone wanted to see him, he was always out to lunch.

If some fancy new drug came on the market, and a prescription for it came into the store, totally baffling my dad, he would call the doctor who wrote it and demand, “Now what the hell is this you wrote up for Mrs. Turner?” They would straighten it out.

* * *

Our school in Oklahoma City originally was known as Our Lady of Perpetual Help Cathedral School, which was a mouthful and then some, but it finally was changed to John Carroll school. I went there through the ninth grade, and then transferred to St. Gregory’s, a boarding school for boys in Shawnee, Okla.

John Carroll was run by the Sisters of Mercy and the priests of Our Lady’s parish. When I started there, the principal was Sister Margaret Mary, the only nun I ever knew who didn’t have the “Mary” part of her name in the middle. She also was the toughest nun I ever met.

The school taught the first grade through the 12th, and Sister Margaret Mary dished out discipline wherever she found the need for it. In the halls, classrooms or playground, she was not above slapping a senior boy around if he got out of line, and no student escaped a paddling or a ruler applied to the palm of a hand if the offense merited it.

Sister Mary Chrysostom, another stern-faced disciplinarian, dealt me a dose of physical rules enforcement in the eighth grade that I have never forgotten. In one of her classes, I sat on the back row and liked to lean my desk back against the wall. She told me countless times not to do it, and one day I did after she walked out of the room through a door behind me. She came back in, saw me, and crushed me on the top of the head with the two text books she was carrying.

Even today my ears ring when I think of it. I don’t recall being hit that hard before or since, and today I blame every mental lapse or shortcoming on that whack on the head. And, it also is a fact that I never lean a chair back without thinking about gentle Sister Chrysostom.

My two older brothers and I drove to John Carroll from Britton, but I also learned to hitchhike as I got older. It was safe then and that’s how I got around much of the time after I transferred to St. Gregory’s to start the 10th grade in 1936.

One reason I transferred was that Joe Trosper, whom I had met in kindergarten and who remains a close friend, transferred there a year before I did. The other reason was that Father Blase Schumacher, basketball coach there, came to Britton one day, found me working alone in the drug store and offered me what amounted to a basketball scholarship to St. Gregory’s.

He said the special price would be $20 per month for tuition, room, board and books. It was an offer my parents couldn’t refuse, so I rejoined Joe and other friends who had migrated to St. Gregory’s.

Joe was one of the best athletes I ever saw, and mainly because of him, we had outstanding teams. On Sept. 26, 1998, our entire 1939 squad was inducted into the St. Gregory’s Sports Hall of Fame. I don’t know why it took so long. Maybe it was because we were great long before the school’s hall of fame was created.

St. Gregory’s is a four-year college now, but in my time there, it was a four-year high school, plus junior college classes for boys who had decided to study for the priesthood. There were fewer than 100 high school students; there were 19 in my graduating class.

* * *

A really ancient priest, Father Blaise, not to be confused with Father Blase, our football and basketball coach, was chaplain of the high school. He heard the confessions of all the Catholic high school boys on a regular basis and it was hilarious at times in that the secrecy of the confessional was forgotten.

To begin with, Father Blaise would hold open the door to his part of the confessional, so he could see who the next victim was. Then, he would talk so loud he could be heard throughout the chapel. It was fun, but only if you were not the poor soul being shouted at: “YOU DID WHAT?” “HOW MANY TIMES?” And so on.

Our basketball teams had outstanding won-lost records, playing mostly other Catholic schools in the state and smaller public schools aroundShawnee. In my senior year, we played Classen, the top high school inOklahoma City. Scared and intimidated, we lost, 19-18. No, that’s not the first-quarter score; that’s the final.

That same year, we earned a spot in the National Catholic High School tournament at Loyola University in Chicago. We won two games, but lost in the quarter finals. Off the court, the seniors on the team managed to slip away from our hotel to see our first burlesque show. None of us told Father Blaise about that. He would have blown the roof off the chapel.

* * *

My favorite priest at St. Gregory’s was the rector (principal), Father Sylvester Harter. He taught English, and all that goes with it, and was an outstanding teacher. There never was a dull moment in his class, and he was the first to tell me I should consider writing for a living. He also told me that although I had the knack, I was lazy. I often thought about that when I was working 80-hour weeks for publishers who didn’t appreciate it.

I made good grades, good enough that my mom said they were good, but that she knew I could do better. So what else is new?

My only real so-so grades came in Physics, taught by elderly Father Hilary. But he knew what was going on among the laggards in the class. Once, during an important exam, he said, menacingly, “Someone is communicating in the back of the room.”

One of the slowest in the class, Louis Collett, said to Frank Rodesney, the smartest among us, “You heard him Rodesney. Be quiet.” It was a feeble attempt to lead Father Hilary’s suspicions in the wrong direction, and even he laughed.

* * *

The class of 1939 held a reunion of sorts on our 40th anniversary, and it was like going back to another world. In our days, there was one building, and it contained the whole operation – dormitories, classrooms, gym, chapel, the priests and novitiates’ quarters, offices, candy store, cafeteria, kitchens, bakery, laundry and whatever.

Now there are separate buildings for most of that, and, as you might suspect, the first new building was the chapel.

We missed getting together in 1989, but in 1998, the school inducted our entire 1939 basketball team into its Sports Hall of Fame.

After graduating in the spring of 1939, Bob Meyers, a teammate, and I were offered basketball scholarships atOklahoma CityUniversity. Joe Trosper was given a scholarship by Oklahoma A&M and coaching legend Henry Iba, but it wasn’t long before we were reunited. Meyers and I were playing as freshmen, while Joe was sitting where freshmen weren’t eligible. He quit and joined us.

* * *

A basketball scholarship at OCU meant tuition books and fees. There was no room and board. It was a private school, associated with theMethodistChurch, and the tuition was $5 per semester hour, which means we weren’t getting all that much from our scholarship. No laundry money, no walk-around money, no money under the table or on the table.

It wasn’t always that way. Bob Meyer’s dad, Tony Meyers, before our time had been Chief of the Oklahoma City Fire Department. He loved sports, and came up with his own plan to make sureOklahoma City University athletes lived well and had money to spend.

He made them part-time firemen. They slept and ate at the firehouses, and were paid to do it. In 1931 the Goldbugs, as OCU teams were called, were undefeated in football, and included was a 6-0 victory over the Oklahoma Sooners.

It probably is the greatest victory in school history. It was the talk of the state, and the Bugs were hailed as giant-killers.

The firefighter plan worked for a few years before some dirty rat-fink blew the whistle and ended it.

There was one thing about our OCU scholarships. Coach Faye Ferguson promised us a job if we wanted to work. I wanted to, and Ferguson kept his promise. My job was running an elevator in the Ramsey Tower, a downtown 30-plus story skyscraper.

In those days there were no automatic elevators, so the operator had to make the car stop and go, and make the doors open and close. We didn’t just run up and down willy-nilly. We had an elevator chief on the main floor who told us when to take off, and could signal us to reverse course anytime he wished. He ran things from a display board that showed him where all six elevators were at any time.

He was called the “starter,” and ours was Woody Renfro, one of the all-time greats of OCU basketball. That was the connection, and I ran my cage four or five afternoons and evenings per week in the off-season.

Once, I asked for a second job, and they sent me to a Piggly-Wiggly grocery store (and I’m not making up that name) to work on the fresh vegetable tables. They weren’t refrigerated. Instead, a fine mist of water sprayed over them constantly, so after about an hour, your hands were scraped raw. I worked there only once, on a Saturday, and never went back.

I learned there that when you add more turnips to the table, you take out all the turnips and put the freshest ones on the bottom, and the old ones on top. It’s the same with all the vegetables, and an hour of that can convince you never to leave the elevators again, even though you risk being chewed out by a bigshot whose floor you missed and forgot to stop.

All the tenants were pleased if you stopped at their correct floor without having to be reminded. I was pretty good at that game, and also pretty good at overhearing conversations. One day, an oil filed drilling company owner named Fain told a colleague the price for drilling a well would be $3 per foot, or $18,000 flat – take your choice. I figured out it would take me maybe two lifetimes to drill a whole well.

The St. Gregory’s combination of Trosper, Meyers and snider at OCU didn’t last into a second season. With one dumb decision, I put my college education in jeopardy, ended my college athletic career, and lost my turning-turning job.

* * *

In the late summer of 1940, I broke a bone in my ankle playing baseball and lost my scholarship to OCU because basketball scholarship players weren’t allowed to play baseball for fear of injury. I did it, I was caught, and I was dead at OCU.

That ended my basketball career, but I had a couple of highlights worth mentioning.

In my freshman year at John Carroll, before I switched to St. Gregory’s, we played a five-overtime game against arch-rival St. Joseph’s of Oklahoma City, and yours truly made the winning basket. A teammate and I took the box score to the Daily Oklahoman, where I told the story to an editor, winding up by saying, “and Snider made the winning basket.”

He looked at me and said, “Why do I think your name’s Snider?”

I was embarrassed, but he said forget it, because it was a good story. It looked even better in the paper the next morning. I carried the clipping for maybe 20 years.

Then, as freshmen at OCU, we played another five-overtime game against Northeastern State at Tahlequah, but I didn’t make the winning basket; the other team did. However, we ended the season beating conference champ Central State on the road.

The thing about that last game was that Charlie Davis, one of my idols at John Carroll and Britton High, was playing for Central. Little did I know that in a few months I’d be going to the Edmond school with him, but not to play basketball.

* * *

Prominent among my memories of OCU is 12-man football, which was born and buried there, all in a matter of a couple of years. Ozzie Doenges was the Goldbug football coach, and he came up with the idea of having a coach huddle with the team on offense during a game.

The coach would call the plays, or comment on the play the quarterback called, then move a few yards behind the team while it executed the play. Ozzie got a few opponents to go along with it, but the idea never caught on. Critics said it was taking part of the game away from the players.

That’s a laugh. Coaches forever have called offensive plays and defensive alignments, but rather than being out on the field doing it, they, or some player, go through all sorts of gyrations to get the instructions to the huddle. Some coaches used to send in a substitute on every play. Some short-waved the strategy.

So, why not do away with the sham, and put a coach on the field? Ozzie still may someday get proper recognition for his idea.

* * *

My mom came close to passing out several times over the years as she followed my early career. It happened at OCU, too, when she learned I was taking a philosophy course at a Methodist school. The reason was, I needed a two-hour course in the early afternoon, before basketball practice, and it was the only one available.

It was more than she could take. She knew OCU by its old name, Epworth College, and she was sure the course meant the devil was after my soul. She insisted I check with our pastor, Monsignor John Mason Connor, before I attended the class. He laughed about it, and said it might not look good if I got too high a grade in the course.

The man teaching the course was a nice guy, and he soon found out I was from what he called “the Roman church.” He needled me on a few occasions, and often taught me Catholic philosophy when he would explain to the class differences in beliefs and practices. I enjoyed the course, and got a passing grade.

I kidded my mom about it, asking her why she didn’t give me the usual business by saying I could have done better. I left OCU with a reluctance not shared by my mother, and on crutches, enrolled inCentralState.

The reason I was on crutches is that the broken bone in my ankle wasn’t discovered until basketball practice started. OCU paid the medical bills, and allowed me to complete the semester. So, it was in January I learned my new school required me to take a basic course in agriculture, plus Oklahoma history.

But about that time, an FBI recruiting team came to Oklahoma City, and I interviewed on crutches for a job in Washington paying $1,260 per year. That’s $105 per month, and all the ice water you could drink. When I heard the FBI was running a background check on me, talking to former teachers, employers and neighbors, I knew I was in, and that I must be someone important.

It turned out I wasn’t. I was hired, and inWashingtonjoined about 50 other newcomers for indoctrination. I managed to hook up with four good guys to rent a big apartment that had a cook-housekeeper left over from the other tenants. We were all assigned to the middle shift in the Bureau’s 24-hour operation, working from11:30 p.m.to7:30 a.m.

It was the ambition of most rookies to become Special Agents, who were paid the incredible sum of $6,000 per year. The hitch was that you had to have a degree in law or accounting to qualify for the training program. So, we all went to law school at night, before going to work. We did our partying in the morning, after work, and slept in the afternoon.

It isn’t easy, but if you work at it, you can learn to drink in the morning.

We also slept on the job, hiding behind piles of fingerprint cards stacked high on top of the filing cabinets. Getting someone to cover for you, you could climb up there and spend the night.

I went to the Bureau in 1941, but in late 1942, received a notice from my Oklahoma draft board to report for an induction physical exam in Oklahoma City. Following the rules, I gave it to my supervisor and an FBI letter went to the board, asking that I be spared, since I was doing work critical to the security of the country.

The board wrote back, telling the FBI it was catching draft dodgers on one hand and breeding them on the other. It was pure Okie, but by the end of 1942, I was back in Oklahoma, sworn into the Navy and on my way to boot camp in Farragut, Idaho. Consoling me, the FBI said I was one of the very few whose draft board rejected its request.

* * *

In my two years at the bureau, I received two raises, first to $1,620 per year, and then to $1,800. I learned to file, helped along, I’m sure, by my years in college, and to classify fingerprints and read them, pursuits in which my college hours didn’t help at all. This was new ground, and fascinating, until the new wore off.

I learned to appreciate big-time entertainment after seeing the likes of the Glenn Miller Band, and Frank Sinatra, in person at D.C. theaters.

I also learned to love the Redskins and the old Washington Senators – “First in war, first in peace, and last in the American league.” They may have been less than spectacular, but on any afternoon, except maybe when the Yankees were in town, you could go to old Griffith Stadium and sit in the bleachers for next to nothing.

And on football Sundays, you could always get a good seat to watch Slingin’ Sammy Baugh and the Redskins. Baugh is one of the best quarterbacks in the history of the pro game, and he also played defense and did the punting, and the punt returning. He came to play.

In 1940, a year before I moved there, the Skins lost the title showdown to the Chicago Bears in an incredible 73-0 game, but came back in the 1942 title game to beat the Bears, 14-9. The Redskins have been my team, in a loose sort of way, ever since.

* * *

The induction physical inOklahoma City featured about 200 men without a stitch of clothing. In line behind me was John McGraw, brother of a close friend of mine, with feet so flat he looked like he had no ankles. Still, they made him go all the way through the process.

It was a good thing for me, I thought, because at the urine sample stop I couldn’t respond. So I gave my little bottle to McGraw and asked him to fill it. He was happy to oblige.

That was that – until I got to boot camp and was told to report to the medical facility. There, I gave a urine sample, and doctors were amazed to see that the blood, sugar, protein and miscellaneous other crap that had shown up in my sample inOklahoma Cityhad all but disappeared.

I couldn’t tell the truth, so I had to do several repeat visits to watch the doctors scratch their heads.

At boot camp, I was named the company mailman, and suddenly everyone looked up to me. The job allowed me to skip a few marching and running drills, and I kept telling our CO, a high school football coach fromTexas, that I had to see to it that the mail got through, on time, rain or shine.

And when the eight-week boot camp was over, the Navy was nice enough to send me home toOklahoma. Comedian George Gobel, stationed atAltus,Okla., Army Air Base, later bragged that not a single Jap plane got pastAmarillo. He had nothing on me. In my years at the Naval Air Technical Training Command base inNorman, no Japanese vessel ever was sighted on the southCanadian River.

* * *

In the spring of 1946, while waiting to be discharged atNorman, a friend and I would requisition, or temporarily steal, a Jeep and drive the short distance to theUniversityofOklahomafootball complex and watch the Sooners in spring practice. In this first season after the war, they had football players like they’d never had before, both in numbers and in quality.

On a couple of these trips we met and talked to a young assistant coach named Bud Wilkinson, and we were impressed. I would meet him again four years later when I was sports editor of theOdessa,Texas, American, and he was head coach at OU, on the recruiting trail. Neither of us knew it, but we were headed toward a friendship that would take us places we never dreamed we’d be.

In the Norman Navy, I went through the 21-week aviation machinist (meaning mechanic) school, and after graduation was given a single stripe, making me a third class petty officer. I also was sent to the officer in charge of personnel at the school. He said he had bad news for me, but that’s just what he thought.

He said he knew how much I’d like to go to the fleet and see action, but it had been determined I was needed more as an instructor in the school than I was aboard an aircraft carrier. He said he was sorry, but it was his duty to order me to report to Building 13 to teach in the basic phase of the school.

I managed to shake off my disappointment over being told to stay inNorman, and I checked into Building 13 and started teaching math. The Navy didn’t know it, and probably wouldn’t have cared, but at every level of my schooling, math had been my worst subject.

Fortunately, inNormanwe dealt only with basic stuff, like fractions, as they applied to tools and nuts and bolts, and other numerical things a mechanic ought to know. In every class I’d have men who never heard of any of this, and others who were math whizzes. I did my best, and we won the war, and that’s all that counts.

At first, I had only Navy men, fresh from boot camp. Then, I had sailors from the Pacific fleet who had earned the right to attend the school. Next were Marines who had fought onGuadalcanaland other hot spots, and finally there were WAVES, the Navy women, and the Marine women who didn’t want to be called anything other than Marines.

On the first day of class with my first group of Marines, I made a mistake. All of them had their hair cut as short as possible, and I was trying to loosen them up a little, and called one of them “Curly.”

He didn’t smile as he fairly shouted back, “My goddamned name ain’t Curly!” Right.

When we had all Navy boots in a class, we thought nothing about flunking those among them who didn’t get it and obviously never would. It was a bad deal for them, because their next stop was an amphibious training base. That meant piloting a flat-bottom boat onto a hostile beach.

But when it came to classes of men who already had been in combat, and who might be sent back to that kind of duty if they flunked, there was no way I’d fail any of them unless they were a total disaster.

The women were treated like the men who hadn’t been in combat. They either made it or they didn’t, and fortunately for them, flunking out wasn’t as big a deal as it was for the men. It wasn’t good, but it didn’t mean invasion training. They also were just like the men when it came to asking where to go on the weekends to find the action.

At Norman, I advanced to first class petty officer but I tried not to let it be known to sailors and Marines who came back from combat in Pacific to attend the school, many of whom hadn’t gotten anywhere near that rank. It didn’t seem right to me that I should outrank any of them, and I was thankful I taught in dungarees with no stripes on the shirt.

My last assignment in the Navy came in 1946. The school was closed, and I was asked to write a history of it. I did it, and I don’t know what became of it. I thought it was pretty good, but I received no “well done” from any admiral.

Prior to that, I helped move the portable part of the base to NATTC Memphis, andNormanwas just a shell. When I visited there in 1999, Building 49, my barracks, was still there, but Building 13 was gone.

* * *

The last thing I want to do is leave you with the impression that I never was exposed to any danger in my Naval career. On the contrary, on several occasions I found myself too close to the edge, and partying to get out of harm’s way. But the thing is, the people I feared might do me in were on our side.

There was, for example, our boot camp leave. When boot training is over, everyone gets a shore leave, and I traveled with Jack Shelton from Farragut, Idaho, over to Chicago, where he lived, and went on to Oklahoma to see my parents. I made arrangements to meetSheltonback inChicagofor the return trip toIdaho.

Everything worked out, and we were headed west, back to the Navy, when the train stopped inFargo,N.D. Shelton, who had an adventurous spirit, was convinced we’d soon be going to sea, and needed extended liberty. He talked to the conductor, who told him there was a late-night train that would get us back to camp about six hours late, but he said he’d write us a note saying we were late because our train was delayed.

That sounded good to us. It was early evening, and when we asked a cab driver where to go, and how to get there, he took us over the state line toMoorhead,Minn. It was the right place. It was like the people there hadn’t seen a serviceman in years.

In the bars, they bought us drinks. The girls asked us – begged us – to dance. We were surrounded. After only 30 minutes, I looked around andSheltonhad disappeared. I never saw him again until about five minutes before the late-night train pulled out. A car full of girls delivered him, and took turns kissing him goodbye.

As we rolled out of town he said, “Tell me the name of this place again.”

* * *

The highway fromNorman,Okla., toDallasis an Interstate now, but in the time of World War II it was a two-laner, US 77. It was a long haul, to Dallas and back, for a couple of bootleggers who were in the Navy and were performing what was considered to be a dangerous but valuable service for our shipmates at the Naval Air Technical Command Center in Norman. Dangerous, but valuable – and modestly profitable.

Oklahomawas a dry state, and sailors always are notoriously thirsty. Thus it was that we were always looking for someone going to Dallas who might bring back a bottle to fight the drought.

One the day my friend Red, fromKansas City, who had a late=-model two-door Chevy, came to me and suggested we make a quick round-trip run toDallasfor booze. He pointed out Thanksgiving was near, Christmas was next, and the sailors were in a buying mood. They could, of course, buy from local bootleggers, but they were looking for a better deal.

How could we turn our backs on ours shipmates? We calledDallasand made contact with a liquor store on the north side. We got prices, marked them up moderately, then took orders from sailors.

We made our first trip on the day after Thanksgiving in 1944, so 2004 is the 60th anniversary of the launching of our enterprise, dedicated to the idea that no Navy man should be denied a ration of rum, or whatever – and neither should a civilian, if we had any left over.

We made the first run, and subsequent trips, without incident. We knew we might get shot down at any time, but we kept the supply line open, always spurred on by the idea that nothing was too good for the boys in blue bell-bottom pants with the 13-button fly.

But the time came when Red and I agreed our luck was going to run out one day, so we gave thanks that it hadn’t, and closed up shop. We had only one more brush with this service. It came when we needed some booze, and gave our money to a sailor named Green. So did a lot of other sailors, but we never saw him again. Neither did the navy, I heard later. He took the money and disappeared.

All I said to Red was, “Why didn’t we think of that?”

* * *

Nobody wins ‘em all, and I had some bad days in the Norman Navy. I recall one incident that never gave me anything to feel thankful for. It was a bummer all the way, and it started one Sunday afternoon in a machine shop where I was watching some men make fancy letter openers and ash trays out of airplane spare parts.

A piece of metal flew from a machine and hit me in the eye, and it wasn’t anything I could just shrug off. I went to the nearest dispensary, where the doctor on duty patched up the eye, and then ordered me to take a series of penicillin shots.

Those were given at Dispensary 21, where all the venereal disease patients were treated, and thus was known as the “clap shack.” Worse, a list of the names of the men being treated there was published and posted every day, as a deterrent. My name went on the list, and stayed there for a while.

Nothing I could do could get my name off the list. The people I talked to said it was tough luck on my part, but orders were orders. Around the base, some people laughed at me, some gave me strange looks, and those who knew me did everything they could do to publicize my plight, including nicknaming me “shack.”

* * *

And speaking of action: Every eighth weekend, I had to do Shore Patrol (Navy cop) duty in downtown Oklahoma City, supporting the full-time SP men, most of whom had been cops in civilian life. I hated the duty, and hated it even more when I was in on one arrest too many one night.

There had been a fight involving sailors in a second-floor pool hall, and I was with the regular SP men sent to clear it up. They arrested a sailor who looked like a born brawler – a huge man with muscles in his hair and a mean look on his face. The SP men asked him if he’d go along with us peacefully, and he said he would.

They told me to take him down the stairs and put him in the Jeep. Down we went, me one stair above him as we walked. Halfway down, without warning, he turned and swung his powerful right fist into my stomach and, I was sure, out my back.

It was two weeks before I could laugh or take a deep breath without big-time pain. It didn’t help that I learned an SP had broken his night stick over the head of the guy who hit me. He couldn’t hurt as much as I did.

After that, I restricted my law enforcement activity to telling sailors to square their hats and threatening to arrest them for urinating in alleys.

The way I looked at it, I done the Navy wrong with my rum running, but the Navy more than got even with me.

* * *

With the war over, I became one of the hundreds of thousands of young men going to college on the GI Bill of Rights, and I was one of the luckier ones. Housing was the big problem on almost every campus, and it was my good fortune to have met Gene Smelser, who also was fresh out of the Navy and was joining the Oklahoma A&M basketball coaching staff under Henry Iba.

Smelser managed to get me a room in the athletic dormitory, Hanner Hall, which was the last place I belonged. With Iba’s OK, he managed to slip me in as the roommate of first a basketball player and later a wrestler.

Smelser’s kindness saved me from having to join a fraternity as a 25-year-old pledge, the only housing alternative I had found. It also freed me to work weekends at the Daily Oklahoman and Times inOklahoma City, where I learned far more about journalism then I did in classes.

I also learned a few things going back and forth toOklahoma City. If I couldn’t bum a ride from another student, I’d hitchhike, and I learned hitchhikers had more to fear from drivers than drivers had to fear from us.

I was riding along one Friday afternoon with a driver who was a fat man who smiled and whose breath was so foul it could kill weeds. We talked, and I guess when he learned enough about me he thought I was a prospect. He turned and gave me a yellow-tooth, poison-gas smile and said:

“Have you been saved?”

I did a quick calculation and figured I needed to ride another 15 minutes to reach an intersection where I’d have the best chance to thumb another ride intoOklahoma City. So I told him I wasn’t sure what he meant.

He said he was asking me if I had accepted Christ into my life and denounced Satan, and if I was ready to dedicate the rest of my life to Christ. If I was ready to do all that, he said, I could be saved, on the spot. I asked him how he’d do that, and he told me.

He said he’d stop the car rioght6 where we were, and I’d get out and kneel on the ground, and he would lay hands on me and save me. He kept talking about it, and he put his hands on my shoulder – while I thanked God I could see the highway intersection ahead.

There was a stop sign there, and when he stopped I was out of the car in a flash, telling him, maybe next time, because I was in a hurry. As I hustled to the other highway, with my thumb out, he was still shouting that it wouldn’t take long.

I still haven’t been saved. I’ve never had anyone in authority tell me my troubles were over. I’ve heard just the opposite.

One cold, snowy day I was catching a flight out ofOklahoma Cityand my mom was there to see me off. She mentioned that the weather was awful, a bad day for flying.

“Well,” I said, “if we crash, at least my troubles will be over.”

She looked me in the eye and said, “Or, in your case, your troubles could just be starting.”

* * *

There is one other point about Oklahoma A&M that needs clearing up. While there, I joined the national professional journalism fraternity, Sigma Delta Chi. There was a certificate, which I framed and have had hanging on my wall all the years since. As my children grew up, they’d see it and ask about it, and I’d tell them I was indeed a member of Sigma Chi, and I’d sing the “Sweetheart” song to them.

It was innocent fun, like telling them the scar on my chest, where I’d had a cyst removed, was a bullet wound I’d suffered in the war. Soon, it was all forgotten.

But then, there was our last child, daughter Mary. She enrolled atDrakeUniversity, and became a member of a sorority. One day, I was watching a touch football game in which she was playing, when a young man introduced himself as a Sigma Chi, and invited me to drop by the house and visit with the members.

He added, “Mary told us you were a Sigma Chi atOklahomaState.” I almost fainted. Mary had remembered all that stuff from years before, and still thought it was true. I certainly never had told her it wasn’t. I still haven’t, and if she reads this, she may never speak to me again.

We had a pool, and Mary and some sorority sisters invited some Sigma Chi over. I had to hide all day. And on two more occasions, this same young man spotted me on the campus and insisted I visit the house. I made excuses and finally, considered escaping the Sigma Chi hoax one more reason to be happy about getting out ofDes MoinesandIowa.

Can Mary sue me for misleading her? If she can, she will.

* * *

After three semesters, A&M gave me a few credit hours for what I had done in the Navy, enabling me to graduate in January 1948. I wanted to stay inOklahoma Cityand work at the Oklahoman and Times, but its best offer was $35 a week as a news reporter. That, I figured, was demeaning to a man who had a degree and a record of having worked for the paper’s sports department on weekends for a year and a half, so I turned it down.

As we Okies say, I managed to find steady work, first with a small office that supplied advertising posters to theaters. I’m talking about the big sheets in theater windows, the work of artists, that showed Johnny Weissmuller in his jock strap, Richard Barthelmess in the cockpit of his World War I biplane or Jean Harlow with cleavage to her belly button. They were what now are expensive works of art, and if I’d have any vision, I’d have stolen the place blind when I had the chance.

I found a night job working in theOklahoma Citysoftball parks, doing the public address announcements and turning the scores. This doesn’t sound like much, but it led to a bonanza. One night, a young man came to the main park, where I worked and asked if he could hook up his popcorn machine and sell popcorn. He said he’d supply everything and give us 20 percent of the gross.

I talked to the boss, C.B. Speegle, a high school coach, about the deal, and he said do it. The first night our take was more than $30. The next night it was more, so C.B. and I got rid of the young man and went out and bought our own popcorn machine. We learned $10 in supplies would pop out to more than $100, and it wasn’t long before we had four machines popping away in other parks.

When the softball season ended, we managed to get the machines into the Oklahoma State Fair, and then into nightclubs. There, the club owners not only shafted us, they let the machines get filthy, so we sold them – took our money and ran. The next summer, the city bought its own machines and C.B. and I were out of the popcorn business. It’s still the best deal I ever was into.

* * *

On the subject of softball, it was important to me and many of my friends in the summers before the war and before the summers I worked at the parks. Softball was coming on strong in Oklahoma City. There were lighted parks and stands, and one of the leagues that was formed was a church league. We thought our church should have a team.

Our church was Our Lady of Perpetual Help Cathedral. You couldn’t get all that on a uniform, so we shorted it to Cathedral, and we told one of the young priests that if the parish would pay our entry fee into the league and buy us uniforms and equipment, we would go into the softball competition and bring home a title.

He said, “Not a chance.”

That was a disappointment, but it didn’t stop us. Pat Horan, a first baseman built like Babe Ruth, and I decided to do it without the parish. Our plan was to solicit Catholic merchants and have them put up all the money. In exchange, we’d put their name on the back of a uniform.

We started with Smith & Kernke Funeral Home, and it was like shooting fish in a barrel. They kicked in and so did other merchants, and before long we were in uniform, with money to buy equipment and pay our way.

A uniform note: The only color available was white, and when I was complaining to the seamstress who was preparing to put the lettering on, she suggested we dye them. What color? Any color, she said. I had an inspiration.

Oklahoma Citywas in the Texas League, and one of the teams that came there to play wasBeaumont, known for its distinctive red uniforms. It was aDetroitfarm club, and I remember Rudy York, a big Indian who played first base and hit a lot of homeruns.

So, we went into the league in red, and everyone remembered us because we had a good team. But alas, we also went into the beer joints in red, and everyone remembered us, because we drank a lot of beer and made a lot of noise. Word got back to the church and we came close to being excommunicated, or so it seemed. We had to promise we’d never again darken the door of a saloon with our uniforms on. Actually, what we did was take off the top and put on a T-shirt.

Charlie Davis, the Britton hero, was on those teams, and so were Francis, Buck and Billy Morgan, Harold McGraw, Phil Braun, Pat Horan, George Hanges, Joe Trosper, Howard Webber and yours truly. Because the manager had to make all the phone calls to keep players informed and I figured if I didn’t do it, it wouldn’t get done, I was the first manager.

Later, Elmo Hunt, older and better behaved than the rest of us, married Joe Trosper’s sister and became manager for as long as the team lasted.

Note: I was playing left field one night and was back-pedaling fast under a high fly, and was at full speed when my head hit a steel pipe running down a utility pole. I never had been back that far, and really didn’t know it was there, and since there was no fence, there was nothing to stop me.

It’s the only time I’ve ever been knocked out cold, and when I woke up I had a hard time figuring out what was going on. Most of my teammates, of course, were laughing. I didn’t see anything funny about it, and I want to make clear I would have caught the ball if it hadn’t been for the pole.

* * *

I continued to look for a job and interviewed with Merrill, Lynch, etc., about a training program. This led to an interview with Federated Department Stores, which was launching a nationwide training program. I wound up at Halliburton’s inOklahoma City, learning the business, from the stock rooms to the sales departments. The pay was good, and that’s about all I care to say about this turn of events.

I prayed for deliverance, and it came one afternoon, when I looked up from putting a shoe (heel in, toe out) on a plump housewife, and there stood Spec Gammon, a college classmate of mine. He was about to die laughing. He was in town with theBorger,Texas, high school football team, which was playing Oklahoma City Capital Hill High that night. Spec was sports editor of the Borger News Herald.

Much later, over a few beers, he offered me a job paying $55 per week, covering both news and sports, and I accepted. The year was 1948. I was back on the journalistic path, and since then, I never have strayed very far from it, if I can count public relations work as journalism.

* * *

Our managing editor inBorgerwas Tony Hillerman – yes, THAT Tony Hillerman – and he was a good man to work with. I hadn’t been there very long when he proved it after I got into a serious situation with the publisher.

He was J.C. Phillips, and most of his employees thought he was in the wrong line of work. He may have thought so, too, because he owned rental properties, and Spec and I made the mistake of renting one of his new duplexes. The occupant of the other half of the residence, incidentally, was a guy who owned a dance studio and spent a lot of time entertaining female dance instructors. He was a good neighbor, but we didn’t enjoy the setup very long.

Spec and I played a lot of golf, and one afternoon we returned home to find it surrounded by fire trucks, firefighters – and J.C. Phillips. Firemen said they found the remains of a cigar in an overstuffed chair. The chair was destroyed and there was considerable smoke damage throughout the duplex. Since I was the only one on that side of town who smoked cigars, I had to be the culprit.

Phillips told us to get our stuff out and not to plan on returning after the place was cleaned up. So, for weeks, Spec and I smelled like smoke and wore some clothes that had smoke discoloration. Of course, we had no insurance.

Phillips didn’t talk to me until Hillerman loosened him up. Tony suggested I write a story about burning down the boss’s house, so I did, and it was fairly humorous, and Tony played it big in the paper. Phillips still didn’t speak to me until after the Associated Press picked up the story and ran it on the state wire. The AP also called Phillips and told him it was good work, and the next time I saw him, he said hello.

* * *

I covered high school football teams from Borger and Phillips, an oil company town, and on road trips the sheriff sent a patrol car and two deputies along with the school buses to make sure there were no problems. I always rode with the deputies, and on two occasions, there were problems.

Returning home one night, the deputies stopped a weaving car, arrested the driver for drunk driving, cuffed him and put him in the back seat with me. He asked me what they had me for and I said, “Sodomy,” and he laughed. Then, before I could say another word, he said, “Watch this,” and slid down in the seat, lifted his legs and kicked the driver in the head with his cowboy boots.

All I remember saying is, “Oh, shit.” The deputies stopped the car, pulled on gloves, and beat the guy to a bloody pulp. He survived and I bet he never kicked another cop.